Description

IMPORTANT NOTE: these plants are NOT IN BUD/BLOOM when shipped. PLEASE look at all the pictures in this listing so you know the condition/size of plant you’ll be getting.

Cymbidium Here Comes Sunshine ‘Tangerine’

IMPORTANT NOTE: these plants are NOT IN BUD/BLOOM when shipped. PLEASE look at all the pictures in this listing so you know the condition/size of plant you’ll be getting. Plants shipped BARE ROOT (unless you order IN POT)

Do you know any siblings (biological ones) that don’t look anything alike, don’t act alike, don’t have anything in common? Some of you, no doubt, are thinking, Yes, that describes me and my brother/sister. How is it that two people who share the genes of their parents don’t seem to have any physical (or even personality) traits in common? The answer may surprise you… It is actually a theoretical possibility that two people who share the same parents DO NOT share the same genes (in this context, the more precise term is ‘alleles’, which simply means versions of a gene). We all know that you get half your genes from mom, and half your genes from your dad. Consider for a moment the half of genes that you got from mom… What about the OTHER half that you didn’t get from her? It is theoretically possible that one of your siblings got the OTHER half of genes/alleles from mom. Now repeat that thought experiment with your dad. You can see that it’s possible that you and your sibling share the same parents, but DO NOT share the same genes!

Since some of you might be confused, let’s try a slightly different explanation. Assume that the 50% of mom’s genes you received are a set we’ll call M1. That means there is another 50% of her genes that you did not receive, which we’ll call M2. Now, let’s call the 50% of genes you got from your dad D1, and the other 50% you didn’t get D2. So your genetic composition is M1D1, while a sibling might be M2D2. In this simplistic view of things, you two siblings share parents, but don’t share any genes (more properly, ‘alleles’)!

OK, some of you who know a bit more about genetics know this simplistic explanation is limited; the reason is something called DNA crossover during meiosis, which is a process of ‘mixing’ genes (quite technical and not something we’ll get into here). But there is a theoretical possibility that this can occur, in the same way that if you shook a jar of 1000 red and 1000 blue marbles, it is, in theory, possible that at some point during the shaking, you’ll find that all the red marbles are at the bottom of the jar, and all the blue are at the top. Note that as you increase the number of red and number of blue marbles, the probability of perfect sorting between red and blue decreases tremendously. It’s one of these things that you may never see happen even if you took a snapshot every second for the age of the universe.

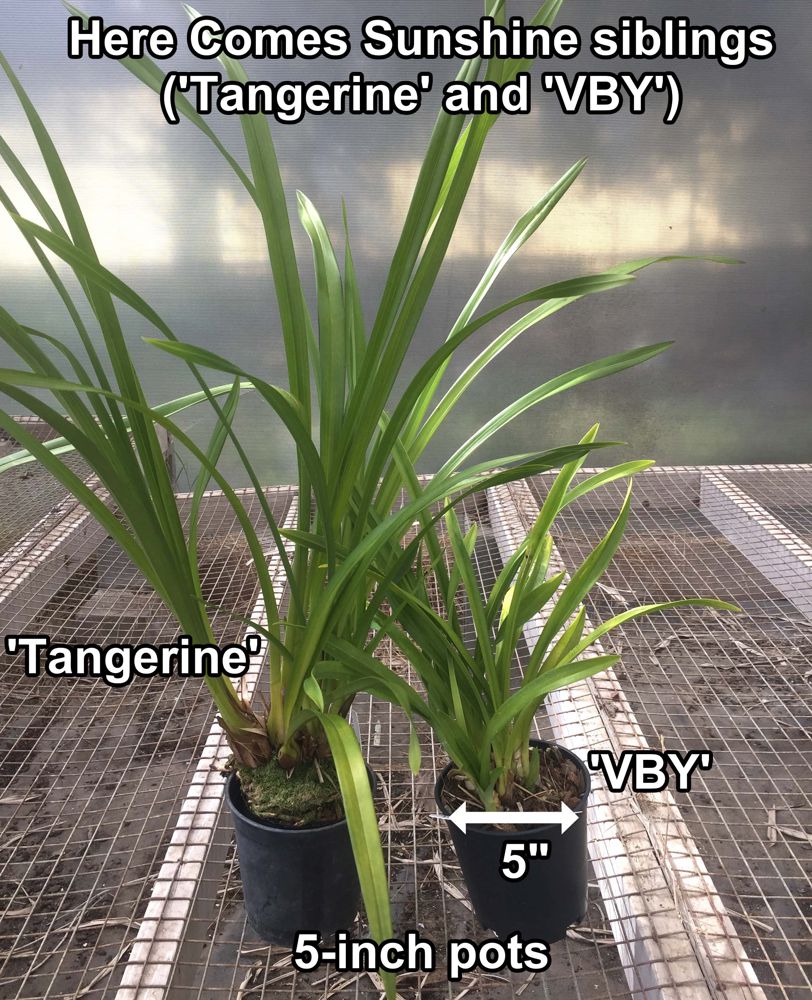

So what’s this got to do with orchids? A lot, actually, since new orchid plants are produced by breeding, and you can see very dissimilar siblings right here in this Cymbidium hybrid called Here Comes Sunshine (yes, it is named after the Grateful Dead song). During the breeding of this hybrid grex (grex is a Latin botanical term referring to ALL the progeny of a cross; think ‘litter of puppies’, and you’ll have the right idea) two of the siblings of this cross, one called ‘Tangerine’ and the other called ‘VBY’ were selected because they stood out from the rest, and were selected for cloning (which is how we can offer them to you).

The thing about these two siblings is they look VERY different from each other. What is most striking is the difference in the size of the plants. ‘Tangerine’ is HUGE, probably the tallest/longest-leaves Cymbidium we have (and we have A LOT). The other, ‘VBY’, is very compact, and has one the shortest leaves of all of our Cymbidiums. Flower-wise, VBY is clearly an alba (i.e., yellow blooms because of lack of expression of pigmentation), while ‘Tangerine’ produces lovely orange (or tangerine-colored) blooms.

One thing both siblings absolutely share is incredible vigor, with VBY edging out its taller sib, but both are very strong growers. Many growers prefer BIG Cymbidiums, and this is probably the biggest (in terms of leaf length) we offer.

This listing is for the ‘Tangerine’ cultivar, but if you’ve read this far, you probably love genetics and want to see it in action in orchids, so it wouldn’t hurt to get BOTH VBY and Tangerine. Or, consider getting VBY for yourself, and getting Tangerine for a sibling whom you love, but don’t resemble in any way.

ABOUT CYMBIDIUMS AND WHY THEY’RE GREAT

Cymbidium orchids are one of the most popular orchid types grown in the world.

Many excellent qualities make them favorites in the flower world:

COLORFUL FLOWERS — Breeders have done an excellent job producing an incredible variety of colors. Colors, spots, splashes: cymbidium blooms have them all.

SHOWY FLOWER SPIKES — Some types hold their spikes erect with big, round flowers and others produce pendulous spikes with graceful arching flowers.

LOTS OF FLOWERS — Some varieties can have 30+ flowers on a single spike! Most modern hybrids have at least ten.

LONG-LASTING BLOOMS — Many modern Cymbidium blooms stay open for two months (or more!).

EASY TO GROW — I usually recommend using reverse osmosis/rainwater/distilled water on orchids when possible, but Cymbidiums don’t seem to need it. They grow outside in non-freezing zones and are used as landscape plants and get the same water as all the other plants. (Of course, using RO/rainwater/distilled doesn’t hurt!)

EASY TO BLOOM — Cymbidiums are not fussy about blooming. They bloom regularly year after year, unlike a lot of other orchids who take up room and board but don’t bloom or do much else! Sort of like kids these days.

HARDY — A mature Cymbidium is a beast of plant. Big, tough bulbs, and thick, stiff leaves make them tough plants that can handle a lot. No shrinking violets, these!

HOW TO GROW THIS CYMBIDIUM

Cymbidium orchids are among the easiest orchids to grow. They grow well in chunky orchid bark (fir bark typically), or thoroughly rinsed coconut husk. Avoid overpotting (i.e., putting the plant in a pot that is too big) — select a pot that is not too snug but also leaves room for growth. Make sure your pot has drainage holes at the bottom. Water twice per week, and fertilize lightly every week or so with any balanced fertilizer. For smaller plants, avoid frost; larger plants can handle near freezing temperatures, but do not leave outside if you grow in an area that gets snow. For blooming size plants (usually three growths/bulbs), allow the plant to experience cooler temperatures (in the 40s F) to set the bud the following season. Larger plants can handle bright light, but younger plants should be grown in bright shade or allowed to receive diffuse light.